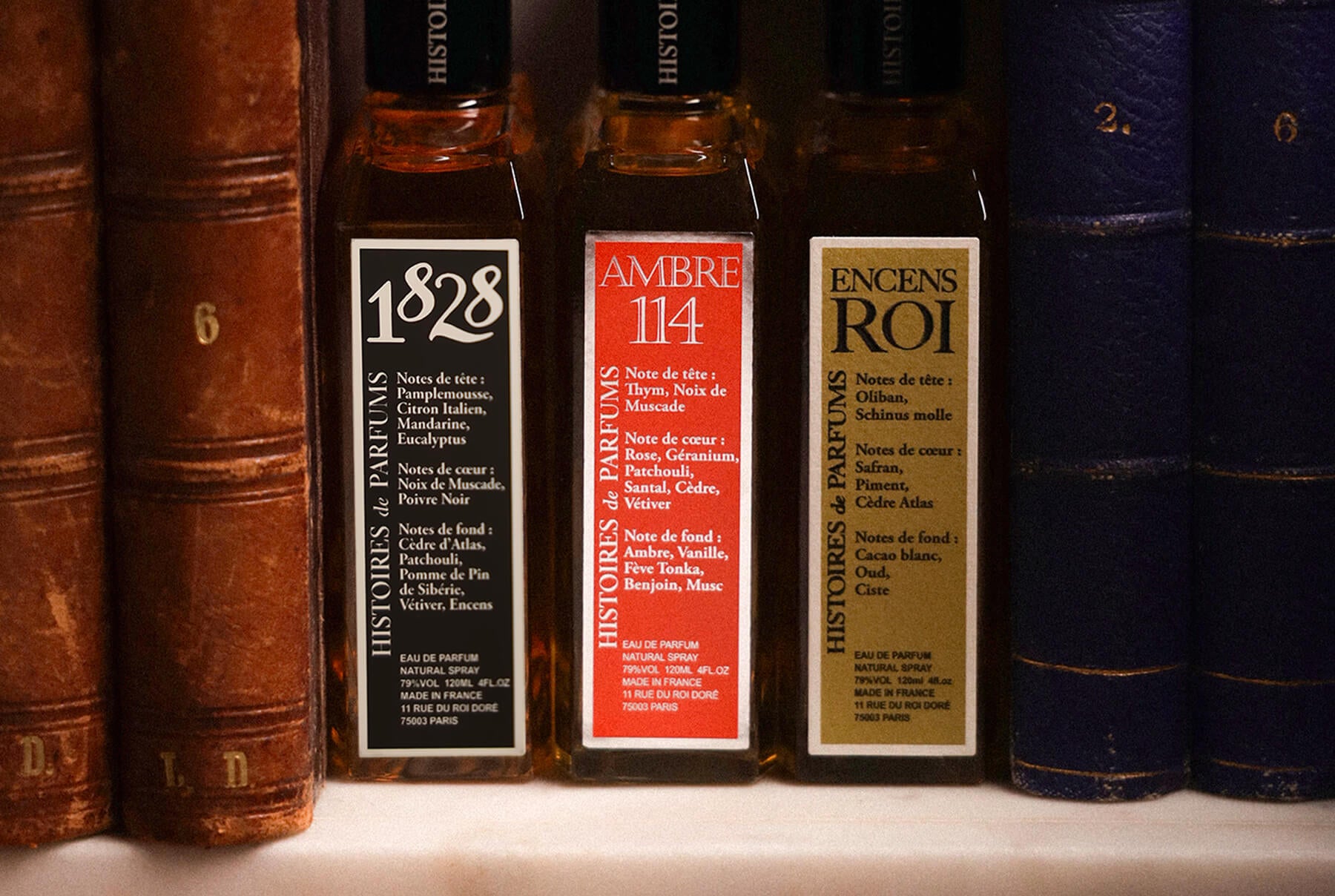

Travelling in perfume

Encens Roi

The first voyage, the most mythical in the perfume industry, linked the Omani coast to the Mediterranean, forming the famous incense route. On the high plateaux of Dhofar, a vast, steep, uncultivated landscape to the south of what is now the Sultanate of Oman, a handful of men slump under the coruscating rays of an imperial sun. Their manqaf in hand, they carefully bark the trunks of incense trees: a series of repetitive gestures handed down from father to son from times immemorial, the blade meeting the bark, the sapwood revealed, the immaculate sap beading on its surface as the harvester waits for it to stiffen before collecting it. It's spring and this ritual will be repeated several times until each man has gathered enough resin to last until the next season. When it is done at last, they hurry, climb down from their altitudes, walk to Iram of the Pillars, the temple-city of incense that the dunes have buried, unload their cargo, negotiate and hand over the fruits of their labour to the merchants. From Iram, some of the incense leaves for the port of Sumhuram, whence it sails to Aden and Socotra then up the Red Sea to the port city of Gaza. The other part is heading inland. A long caravan is formed, crossing Sobota, climbing towards Marib, the capital of the kingdom of Saba, before stopping off in the land of the Minaeans, which the mythical road bisects. From there, for seventy days and almost as many stages, merchants and spices, beasts and sands rub shoulders in the Arabian desert, crossing Al-Ukhdûd and Tabala, skirting Mecca by a few days, persisting against the boldness of the elements as far as Yathrib, today's Medina, before reaching Thapua, Ma'ân and Petra whence it is possible to reach Amman, Damascus and Gaza. It has been nearly three months since the resin was harvested and still it sails to Rome, from where it spreads to the four corners of the Empire where it will be sacrificed to idols, used to perfume banquets. Its lemony, mineral scent, the quintessence of its native land, has become synonymous with divinity. The Empire collapses, Christianity takes over its use, and frankincense leaves the orgies for the cathedrals and the coronations of Catholic kings and Byzantine emperors. It becomes known as frankincense, the true, immaculate incense, the sap of the Boswellia Sacra, the sacred tree, that which cannot be defiled, the use of which is consigned to the praise of God, Allah or Yahweh. Such was its history forged. Thousands of years later, the descendants of the first incense gatherers repeat the same gestures on the same days. The cities of yesteryear have lost some of their splendour, aeroplanes have replaced the formidable caravans, but the fragrance of frankincense remains intact, hypnotic, mysterious and eminently spiritual. This is Encens Roi.

Ambre 114

Amber is a figment. It is ambergris, cistus, vanilla, myrrh and benzoin, opoponax and tonka bean, it is everything and nothing at the same time. Amber is a construction, an accord first conceived by Coty in his Ambre Antique, an amalgam of precious balsams reserved by the ancients for kings and gods. However, if we had to focus on two materials, it would have to be cistus and vanilla - the beginnings of an intercontinental journey spanning several millennia. Here, on the borders of the Near and Middle East, Tushratta, King of Neherim, dictates a letter to Akhenaten. The scribe carefully transcribes the king's words onto the clay tablet, proposing that the pharaoh marry his daughter. In addition to the tablet, a series of gifts are sent to the capital of the new ruler of Egypt, including an oil scented with labdanum, no doubt extracted from some Syriac bush. Later, deep in the Nabataean hold, a few men roll the labdanum gum between their fingers and place it on embers to extract its fragrance, volutes upon volutes filling the entire space of their homes with their thick, animalic and balsamic fragrance. In Crete, for almost 4,000 years, shepherds have been harvesting it from the beards of their flocks: the goat grazes in the scrubland, the scent of labdanum attracts it, it rubs against the bushes and returns to the barn, its coat flecked with an exquisite sap that is collected with a fine-toothed comb. Wherever it grows, on every rocky escarpment or scrubland, labdanum is harvested for a multitude of uses: the Carthaginians burnt it for their dead, the Cypriots made perfumes from it, Westerners burnt it in their homes to protect themselves from the plague; it is the resin of kings, one of those mysterious balsams whose name the Bible deliberately withholds yet whose memory tradition preserves. However, it is not amber yet – it would need vanilla to become so, which originated on another continent, in a drastically different environment. There's no question of scrubland, maquis or desert, here all is dense, bushy, suffocating, perspiring greenery; intermingled shades of all greens, the chirping of exotic birds taking refuge at the top of cyclopean canopies: the cradle of the Totonac. For almost a thousand years, they have been harvesting vanilla, the fruit of an orchid that a hummingbird pollinates in flight. It was a cultic secret which they guarded preciously until the arrival of the conquistadors: captivated by its sensual aroma, the Spaniards brought it back to Europe, where it acquired a noble reputation. The prized possession of princes of all courts, vanilla flavoured their drinks as much as their dishes, until a slave on Bourbon Island, the young Edmond Albius, imitated the delicacy of the hummingbird and invented the manual pollination of vanilla, enabling it to be cultivated on a large scale. From Bourbon Island, it spread to Madagascar and the Comoros, colonising all the colonies of the French Empire, intoxicating the bourgeoisie, newly invested with the powers of the beheaded nobility. In 1876, it was synthesised, and in 1905 the first true amber was born, a fanfare of numerous balsams in which labdanum is on a par with vanilla. Since then, these two ingredients have been the mainstay of all ambers, no matter how many ingredients are used to adorn them... be they 114.

1828

Was Jules Verne a stranger to travel? Had he travelled to the ends of the earth to invent a journey twenty thousand leagues under the sea and to the centre of the Earth? Fuelled by the scientific, geological and geographical discoveries of his time, Jules Verne aroused a feverish enthusiasm in Europe for far-off lands, long before the globe-trotters of our century. Line afetr line, he traced in ink the contours of a limitless world, detailing, like the Marco Polo of the industrial revolution, the customs of little-known peoples and the topography of their lands, delighting the most insatiable explorers by providing them with a quasi-photographic account of unattainable frontiers: that of the great abyss and that of the fantastic core of the Earth. What emerges from his writings is a phantasmagoria impregnated with reality, a kind of delirium deeply rooted in matter, their osmotic encounter generating that energy felt by those who escape and confront their stranger: a dreamlike impression, specific to travel, of knowing a space without recognising it. Montaigne said of travel that it was "a double encounter, with others than [oneself] and with [oneself], as another in the eyes of others": travel has no other purpose than to obtain an intimate truth about the nature of being, the essence of life. Jules Verne's spectacular settings, emerging at the height of an era of scientific and technological dazzle, not only update the mythical limits of the ancient epics of Ulysses or Marco Polo, but also push them further to open them up to an allegorical field, as if reality were no longer enough to quench the thirst for elsewhere, the need for a Platonic "wandering" that all men necessarily feel. By merging the real and the imaginary, Jules Verne made travel a link between the noumenon and the phenomenon, between the world of subjects and the world of objects, between the infinite and the finite, between visible nature and that which is invisible because it is invented, suggesting the multiple possibilities of being and becoming that are open to those who dare to cross from one shore to another. Similarly, since its invention, perfume has also played the role of a manifestation of another world. Confronted with the impermanence of the smoke of incense, humans suddenly remember their own, while the remanence of its fragrance invites them to contemplate the permanence of a force beyond themself: the gods of the Egyptians, the Brahman of the Hindus, the Holy Spirit of the Christians. It is in this way that travel and fragrance are consubstantial, both instruments of mediation so that the traveller and the perfumee can complete their aufhebung, the overcoming of contradictions that their wandering will have crystallised, suppressed and sublimated. Unless, on the contrary, they are recursive, destined to be continually repeated, volute after volute, detour after detour, as if the value of the journey lay not in reaching a haven but in the impossibility of a return, binding the traveller to be so torn by their drifting that they forget their past and abandon the expectation of a future, distending time to better savour, with an Augustinian attention, the fleeting joys of the present that is constantly offered to them anew.. 1828 is the expression of this impulse.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.